The Foundation

A lot of my posts have been successes that I had, but life rarely, rarely, felt like success. Progress and change occur the same way you climb a mountain: you huff and puff and wonder if you’ve actually moved at all. But once in a long while, there’s a parting in the trees, and you can see a marvelous view.

Boys’ Club was a lot like that.

One of the early weeks of teaching, my seventh-grade boys created this contraption, so that when I walked through the classroom door, a venomous snake fell on me. It was a brilliant feat of the engineering, but I was on my teaching A-game. I did not react in anyway, just calmly told the boys to go take the snake back to the forest and to treat animals with more respect.

We can assume they didn’t particularly care for me.

I taught my eighth graders the vocabulary word “unlucky”, and from then on, every time I walked into the classroom, my boys would moan, “how did we get to be so unlucky to have you as our teacher?”

And I made some big mistakes with them. One day, some of my boys were sprinkling sand in their classmates’ bags. For those of you who have not taught seventh graders, this is really not a big deal. As I told them to clean up the mess, another, not involved boy walked into the classroom and shoved me, hard, because I was in his way. I immediately left and got the principal to discipline the student for pushing me.

The principal came in, and immediately the students started telling him about the sand in their bags. I tried to interject by explaining that I was handling the sand, but I had been pushed in an unrelated incident, but the voices of seventh-grade boys outranked me. The principal told me that I was confused about what had happened, that I hadn’t been pushed, and proceeded to very harshly discipline the sand pranksters.

But as the weather warmed, their hatred of their first female teacher thawed.

The ninth grade boys figured out my name is close to the Nepali word for bananas, so they started calling me Miss Banana (in Nepali) and assumed I couldn’t hear the difference. I spent a few days wondering if I was supposed to be offended, and then one day the boys’ ring-leader wouldn’t stop chatting in class. “Mr. Coconut, sit down and listen,” I said. The poor boy fell out of his chair in shock.

From then on, the boys called me Miss Banana and I called them all various fruits. All in good fun. That was the first time I saw it: a spark that maybe we could have great relationship.

The real breakthrough, though, came on the same hill I wrote about here. A few of my more unruly students were Dalit (“Untouchables”) who lived in that community. One day, I informed them that I would be visiting their home for a home visit that afternoon. Most students have a reaction when I tell them this: excitement or nervousness. These boys had no reaction at all.

When I showed up that afternoon, no one was home. A neighbor pointed me to the black smoke of the brick kiln, where the boys were hard at work, covered in dust, making bricks. They were very surprised to see me, and even more so when I asked them to show me how to make bricks. Because it is such dirty work, brick making is often seen as one of the worst jobs to have. After getting thoroughly saturated in brick dust, we made it back to their house.

At first, it was very awkward. Every conversation I tried to start was met with a one-word answer or, worse, a shrug.

Until one of them asked me if I had brought my family photos. I had a big stack of photos I had printed off the night before I left America, and my students absolutely loved seeing them. Pictures are extremely rare in remote Nepal, so it was considered a big treasure to be able to see them.

I told the boys I hadn’t brought them, but I promised to bring them to school the following day. The boys didn’t react.

I don’t know why I did it–it was a full 30 minutes away–but I stood up and told the boys I was going to go get my pictures from my house and bring them back. It didn’t make any sense; I think I just wanted to see an emotion other than apathy on their faces. I half expected the boys to be gone by the time I got back.

But when I trudged back an hour later, the boys were still sitting in the same positions. I passed them the envelope of photographs, and moved to sit between them, so I could explain the pictures.

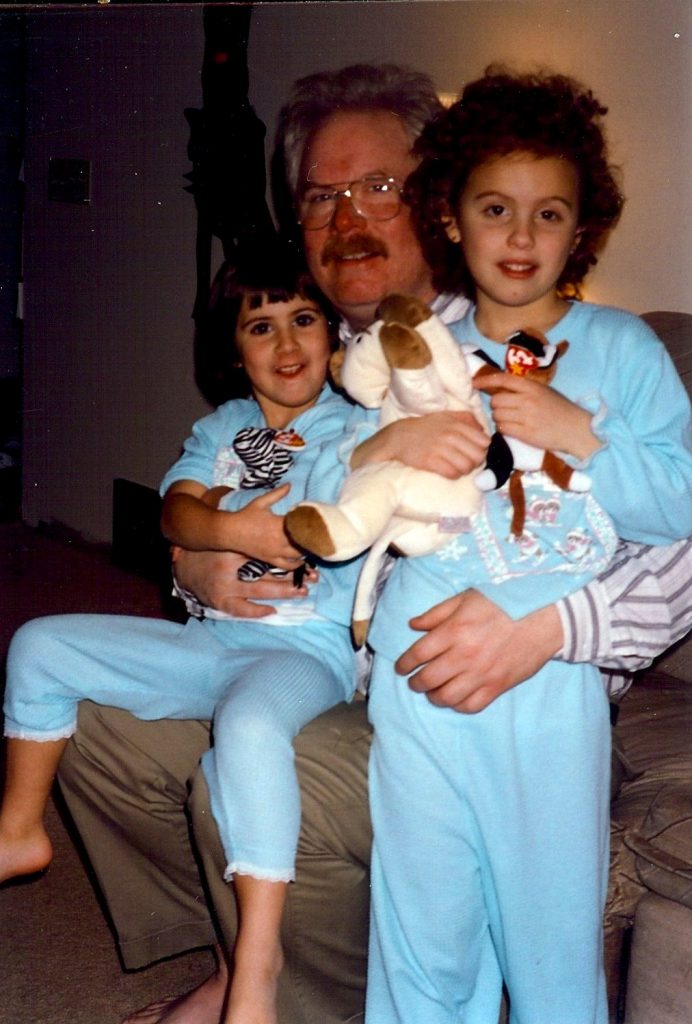

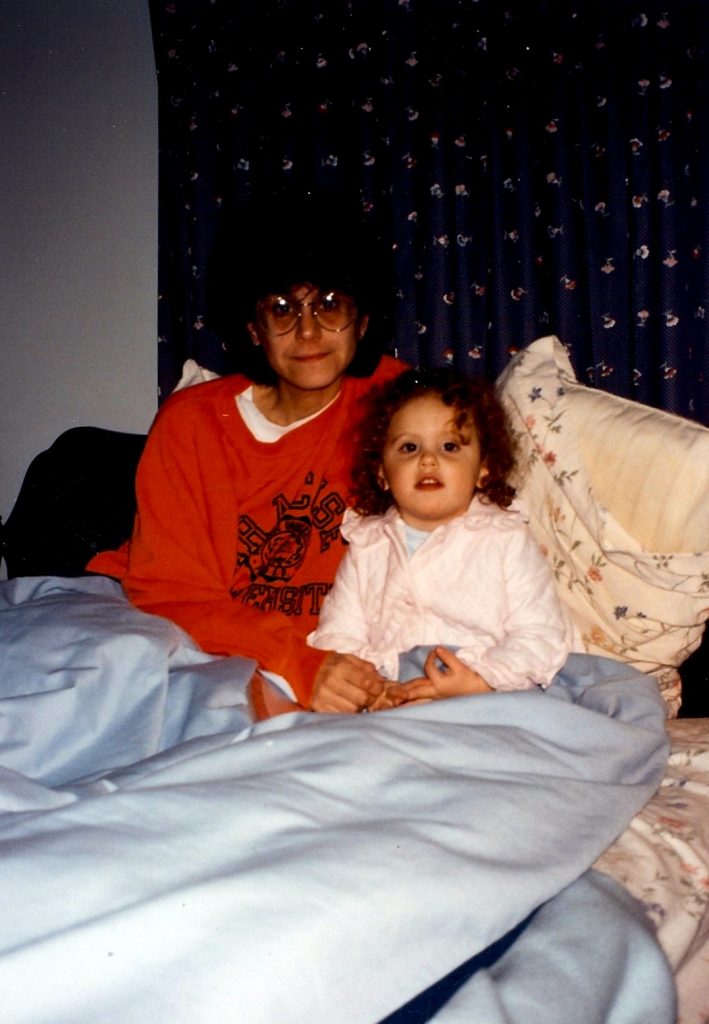

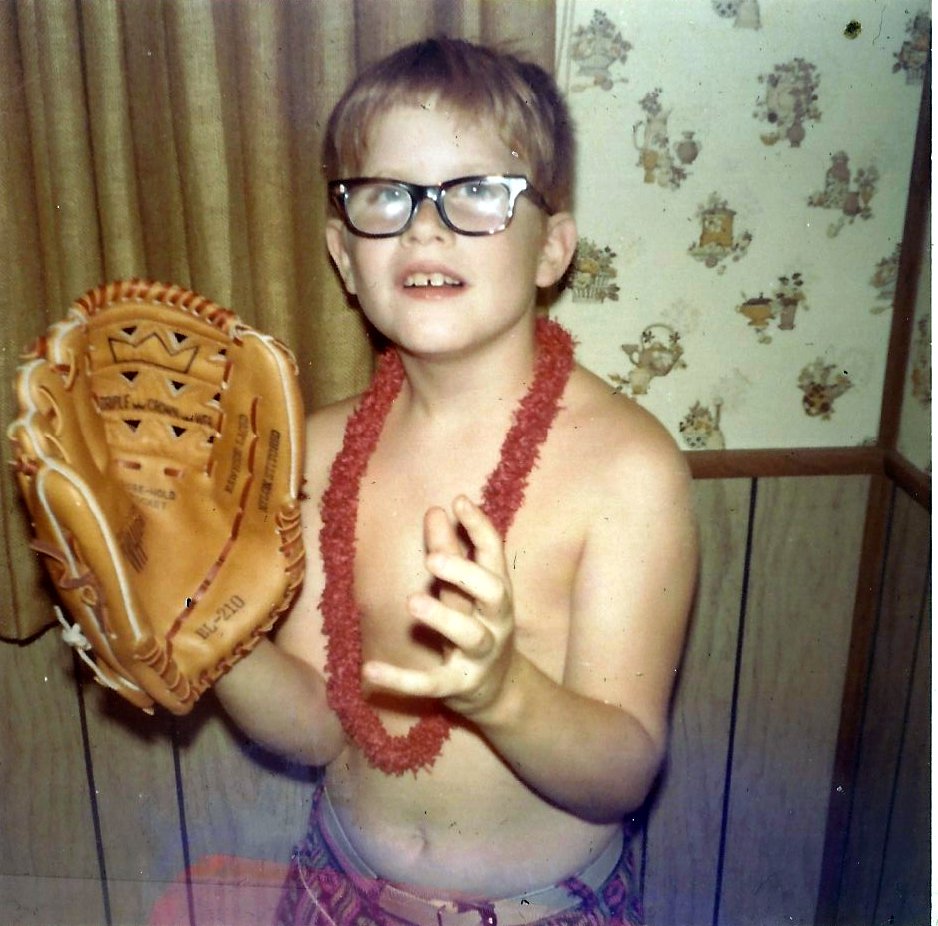

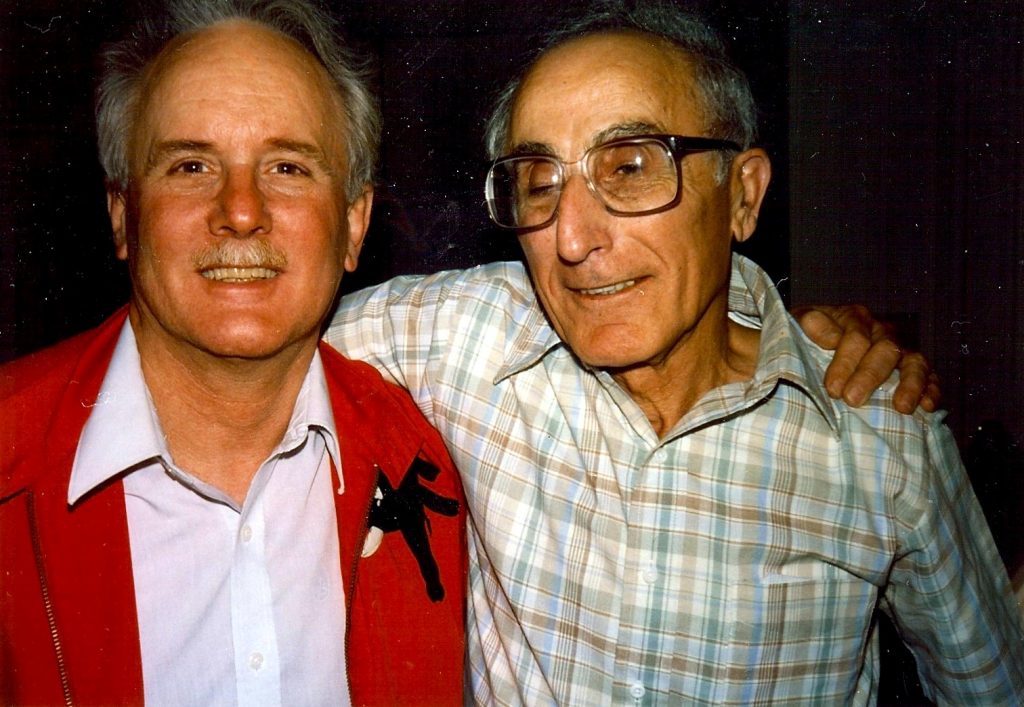

I have never seen people hold objects with more care. They gingerly grasped them in their hands, as if these photographs were priceless works of art. They laughed at the photos of me when I was a little girl. They exclaimed when they saw my sister’s bright red hair.

When I left, I told them they could keep a picture if they wanted. I explained I could print out more when I got back to the US. Each family of boys took one:

My dad as a boy

My grandfathers

Walking back to my house, I stopped at the top of the hill to watch the sunset. My mind was racing. I knew then, that our relationship had fundamentally changed. I don’t know why, but for whatever reason, but when they touched those photographs of my family, they began to trust me. It was immediate; it was startling. It was the beginning of Boys’ Club.